The future of movies, viewed through the lens of the past

Back to the future

Cinema’s yesterday holds clues to its tomorrow

Exclusive to MeierMovies, June 2024

Exclusive to MeierMovies, June 2024

“Movies are just a little bit over 100 years old,” Christopher Nolan reminded us upon accepting his directing Oscar for Oppenheimer. “Imagine being there 100 years into painting or theater. We don’t know where this incredible journey is going from here.”

No, we don’t know, but we can guess. And for assistance, we can turn to the place that has always helped predict the future: the past.

In December 1895, Auguste and Louis Lumière invented the cinema, or so the story goes. The truth is Eadweard Muybridge had used his zoopraxiscope at Chicago’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 to project a series of photographs, creating something similar to today’s stop-motion animation. And Woodville Latham can also claim to be the first to show films on a screen to the public, in New York City, several months before the Lumières’ Paris debut.

But as is the norm for technology, the invention preceded the unveiling by a few years. Inspired by magic lanterns and Muybridge’s horses, Louis Le Prince, a Frenchman working in Leeds, England, arguably invented motion pictures when he captured, with a single camera, a couple of seconds of people dancing in 1888 and then projected the footage. But because of his untimely death, Le Prince was never able to publicly share his work. So what happened between the invention and the social artform’s launch seven years later? Answer that question and you might get your prediction for film’s future.

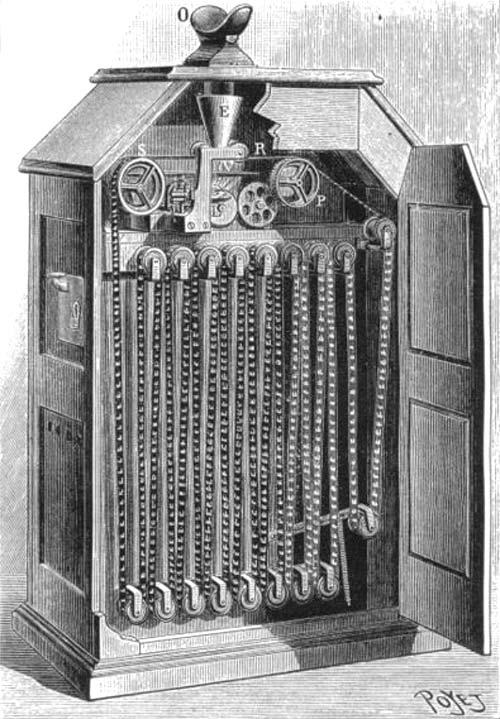

The invention initially went nowhere, with Englishmen William Friese-Greene, William Crofts and Wordsworth Donisthorpe, and others, all experiencing limited success. Meanwhile, French scientist Étienne-Jules Marey continued perfecting his chronophotographic gun, which he had used as early as 1882 to capture 12 photos each second. But it was Thomas Edison who finally broke through, in 1894, when 10 of his kinetoscopes were unveiled in New York City. He and his employee William Dickson (who would assist Latham in his projections a year later) designed the machines for a single person to look through a peephole. Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope notwithstanding, Edison claimed the first public exhibition of motion pictures.

But unlike the Lumiere presentation a year later, this was a lonely experience, a performance for one, a novelty in a nickelodeon. Nowhere to be found were the laughs, applause and shared experiences the cinema would soon foster. Absent was the collective, theatrical joy.

Sound familiar? Today’s moviegoers are looking more and more like those of 1894, except with even more isolation, as each living room becomes a personal nickelodeon. Eschewing theaters, the general public now prefers to stream at home. With theatrical windows shrinking or becoming non-existent, one doesn’t have to wait long, or at all, for new films. And the astonishing improvement in TV and web dramas over the last two decades, though a boon artistically, has further encouraged the trend toward individual viewing. If film historian Charles Musser was correct when he said that “modern cinema began with the nickelodeons,” he might want to add, “that’s where it will end.”

There’s a reason Gone with the Wind’s box-office record (adjusted for inflation) will likely never be broken, despite the U.S. population more than doubling and the world population quadrupling since that film was released in 1939. Theatrical audiences are increasingly homebound, by choice. And the next phase is almost here: virtual reality and the metaverse, which will encourage people to share their viewing experience with no one, as headsets allow complete immersion and quarantine. Eventually, inevitably, social interaction will be removed almost entirely from motion pictures, and substantially from life itself.

Admittedly, as with Mark Twain, the report of the death of cinema has been exaggerated before – for over a century. The artform has survived threats from radio in the 1920s, television in the 1940s, personal computers in the 1980s and the internet in the 1990s and beyond. And just as the industry fought these intruders with Technicolor, 3-D, wider aspect ratios and provocative, adult-oriented content (upon the collapse of the Production Code), it could invent new tricks to get people out of their homes. (Remember 4DX?)

But something feels different now, as if the human brain is being reprogrammed by our addiction to cell phones. (You don’t even have to drop a nickel in the slot.) Add in the eventual ability of VR and the metaverse to place the viewer inside the movie and select the outcome, and the seeds of the collapse of traditional cinema have been sown. Sprinkle in AI, and the dehumanization of a profoundly humanistic artform is complete.

Not everyone sees it this darkly. Some argue that the metaverse could facilitate new moviegoing formats, similar to Zoom, during which audiences thousands of miles apart enjoy a shared screening, albeit virtually. And Entertainment Weekly’s Brian Raftery, in a March 2022 article, speculated that the new technologies could co-exist with traditional screenings: “Does that mean you might walk into a theater in 2032 wearing your VR or AR gear, watching a movie while simultaneously hanging out in the metaverse? Perhaps.”

Others eagerly await advancements in 360-degree cinematography, which could further revolutionize the industry while rendering aspect ratios irrelevant. But the practical applications of these potential advancements still seem geared more toward the experience of an individual than an audience.

It’s a frightening prediction, not just for cinema purists but for the “ancient race” that Harmonica described to Frank in Once Upon a Time in the West. Forgetting they were facing death in an impending duel, the enemies bonded briefly over their fear that modernity would kill off humankind as they knew it.

Frank and Harmonica are long dead, as are the actors who played them, so the future of movies, and the society that creates them, isn’t their concern. Perhaps the same can be said for the elderly and middle-aged among us. But for you younger moviegoers, this will likely be your future. It would behoove you to prepare.

Ready, player one?

© 2024 MeierMovies, LLC

Featured image (iStock 1295289697) by Dilok Klaisataporn