Psycho

Psycho, 1960, 5 stars

“They’re probably watching me”

The act of observation in Hitchcock’s Psycho

Exclusive to MeierMovies, 1994

Exclusive to MeierMovies, 1994

When Psycho was released in 1960, it made an indentation upon the minds of the American audience as few films had ever done. It broke a tremendous amount of new ground for mainstream U.S. cinema in terms of perceived violence, sexuality and crime. Never had the heroine of a picture been killed off halfway through the movie. Never had an audience had to deal with transvestism, Freud and repressed sexuality all in one evening at the local theatre. Amazingly, few, if any, moviegoers had ever even seen a toilet being flushed on screen. Therefore, these minor points of plot, as Hitchcock saw them, distracted the audience from the true importance of the film, its style. And it is that, observational, even voyeuristic, style that is the film’s ultimate statement and one of its continuing legacies.

A director worrying about story is comparable to a painter wondering whether the apple he is painting is sweet or sour, Hitchcock said. Any story can be told; what makes it noteworthy is the style in which it is told, the director thought. Therefore, according to that definition, the shocking nature of Psycho’s plot should forever be secondary to the style the creator chose. And so, being a purist, Hitchcock chose a subjective camera. This style had been his favorite for years, allowing the audience to observe the action along with the characters. Hitch would typically begin with a close-up of a person observing a scene, then cut to the scene itself, then cut back to the close-up, this time with the person’s reaction. The director, therefore, was merely recording the scene, almost dispassionately. But he also lets the audience identify with the character and, in the case of Psycho, feel as if they are being drawn into this strange world of Norman Bates by being able to spy on it in a slightly voyeuristic way.

But an analysis of the subjective style only scratches the surface of a film literally packed with images and themes related to voyeurism, eavesdropping, observation and “being watched.” As Norman says to Marion Crane while his stuffed birds peer down on him, the cruel eyes are studying you. He is speaking of a mental institution, but the metaphor is unmistakable – he’s the one being watched, by his mother, by his birds, and by us, as we spy on his world through the convenience of Hitchcock’s camera. In addition, Marion, the other characters, and, indeed, the audience, are both watching and being watched. This observation theme is the most obvious message of the film and can be expounded upon almost endlessly. What follows is a summary of the most interesting elements of this aspect of the suspense classic.

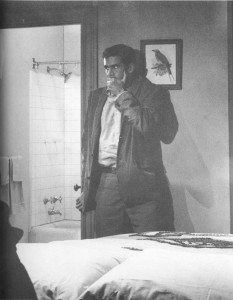

The strongest examples of this theme are impossible to ignore, even if one is wrapped up in the bizarre details of the plot, which most moviegoers were in 1960. The first two surface as obvious elements of Norman’s personality and the third as Hitchcock’s means of introducing us to two of the characters at the movie’s start. The director begins the film with a long helicopter sweep – the only element captured more successfully by Gus Van Sant in his inferior 1998 remake – and then cuts to an open window. He then zooms in, as if we, the audience, were literally voyeurs spying on this meeting between two lovers in a hotel room. The frank sexual nature of the scene added tremendously to the voyeuristic effect in 1960 and set the tone for the rest of the film by making audiences repeatedly feel as if they were in a place, overseeing and overhearing events, that they were not supposed to be. The second obvious moment of observation comes when Marion overhears Norman fighting, or so she and the audience thing, with his mother. It is not so much voyeurism as unintentional eavesdropping. Again, Hitchcock is slowly revealing this strange world to us, not by traditional use of the camera, but by letting us identify with a character and feel the discomfort of that character overhearing a private conversation. The third and by far most overtly voyeuristic moment of the film – or any film of the day – comes when Norman spies on Marion through the hole in his parlor wall. To achieve this view, Norman removes a painting of Susanna and the Elders, the biblical story of a bathing woman overtaken by voyeurs who had been aroused while spying on her from a secret place. This and the subsequent shower murder represent the rape of Marion. This and the overall sexual nature of the film’s plot and style will be addressed later.

Before moving on with more images from the film, one should consider Hitchcock’s technical brilliance and how he used the camera to heighten the observational feel of his work. The director was no stranger to this feel. He used it extensively in Rear Window and other films and drew immense pleasure from letting the audience have little bits of information while concealing them from the characters on screen. He felt this both created tension and aroused a feeling of helplessness in those watching because we could not effect a change. Therefore, Hitchcock’s style served Psycho beautifully. He used not only the subjective style, as mentioned before, but a 50mm lens on a 35mm camera. This was the closest approximation of the human eye’s field of vision Hitch could get. In other words, when Norman peers through the hole at Marion, we see exactly what he sees (minus, of course, the color, perhaps the only distortion of our gaze into this new world, but a necessary distortion in order to capture the dark mood of the movie). Hitch also used a forward-moving camera instead of exclusively cutting from frame to frame, as if the audience were walking into, say, the Bates house, with Lila. Finally, the high-angle shot surfaces several times, as when Norman carries the corpse down the stairs and comes out of the bedroom dressed as mother to kill Detective Arbogast. In these instances, we become slightly disengaged from the action, a little embarrassed to be there, and a bit scared of being discovered. This shot both adds to the feeling that we, the audience, might actually be there and lets us analyze the behaviors of the characters as if we were slightly removed.

Despite Hitchcock’s assertion in interviews that the style, not the story, is by far the most important part of a film, even he would have to admit that Psycho’s story lends itself perfectly to the observational approach he takes. The movie was based on the novel by Robert Bloch, which, in turn, was inspired by the actual murders of Ed Gein, a psychopath from rural Wisconsin who was convicted in 1957 of killing his family and many others. His escapades, which make Psycho look like a bedtime story, included incest, transvestism, graverobbing, cannibalism, necrophilia and torture. However, the reaction of the town in which he lived was one of disbelief. How could this have happened, they asked themselves. So they had to erase the crime, at least in their own minds, as the psychiatrist at the end of Psycho says about Norman. The locals joked about Gein and played the roles of observers, coming to Gein’s house to peer in and get their kicks, following his sentencing to a mental institution, where he died in 1984. The villagers had discovered a strange new world, but they did not want to get too close or it might reveal something about the nature of their peaceful little town or even themselves. So they played voyeurs, just as we do in Psycho. Bloch, of course toned down the details of Gein’s crimes, putting the emphasis on the mother fixation, the Freudian sexuality and the shower murder. But the observational motif is there in Gein’s story, in the Bloch novel and in the Hitchcock film. It would, by the way, take more than ten years for many of the true horrors of Gein to surface, in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Another place in which this theme can be found is in the lines themselves as written by Bloch and screenwriter Joseph Stefano. The scene with Norman and Marion in the parlor is packed with them. Marion wants to escape to a “private island,” presumably where she cannot be watched. Norman shows a glimpse of the mother side when he speaks of a mental institution. “The cruel eyes studying you … the laughing and the tears … my mother there?” he asks. At one point, after showing his hatred of her, he leans back in his chair, allowing the staring bird in the background to dominate the shot. “But I know I can’t,” he says of his contemplation of leaving her. It’s as if the mother is watching again through the eyes of the stuffed bird,

which moments before he had compared to her. The final scene too is a commentary on the feeling of being watched:

“They’re probably watching me. Well, let them. Let them see what kind of a person I am. I’m not even going to swat that fly. I hope they are watching. They’ll see. They’ll see, and they’ll know, and they’ll say, ‘Why, she wouldn’t even harm a fly.’ ”

Incidentally, it makes the audience feel somewhat relieved when we, having been the fly on the wall throughout the entire picture, realize we have escaped unharmed too.

Before concluding with a brief discussion of the film’s sexuality, the image of the eye cannot be ignored. In short, it is the ultimate symbol of watching and being watched. Every character, at some point, is being studied, except for, perhaps, the policeman who questions Marion on the road. He is the only one who is constantly watching both Marion and the audience, never being watched himself. And what does he wear throughout his time on screen? Sunglasses. In addition, when Marion is killed, it is the dead stare that affects us more than even the murder. Life is running out like water down the drain, and we can literally see it in her eyes. Finally, the haunting, hollow eyes of the corpse in the fruit cellar, maybe the most chilling image of the film, come to life under the moving light of the swinging bulb. The stare of death grips us, just as it does when Norman ends the movie with his evil gaze. That gaze, even for us voyeurs, seems a little too close for comfort, especially when the superimposed skull is slightly visible, a choice Hitchcock made so late that some prints do not contain it.

Today the sexuality of Psycho seems fascinating but not shocking. But in 1960, its shock value was a chief reason the audience felt like voyeurs. They simply were not used to hearing discussions of transvestism, seeing women lying in bed in only their underwear and witnessing the normal activities that take place in bathrooms. The extremely brief, soft-focus nudity (if it is there at all) was rather eye-opening in 1960 as was Janet Leigh walking around in a bra and slip. The spectacle was even a bit much for Leigh and the film crew, who went to great pains to keep the actress covered by moleskin cutouts. The presence of the nude body double on the set was foreign enough to some to create a rather surreal atmosphere on the set as well. This was unusual filmmaking, and the audience knew it. The Freudian overtones are abundant, especially when Lila visits the house, taking us along for the visit. Norman’s room is that of a little boy, stuck in an infantile stage of sexual development. The book Lila discovers might also be shocking to her, judging by her curious reaction and the musical crescendo. Could it be pornography, as the story of Gein and Bloch’s novel suggest? We, as the audience, are eager, and a bit embarrassed, to discover, just as Lila is. Ultimately, though, the sexual theme is played out through the murder, or rape, of Marion, in the shower no less, and the impression of transvestism and incest. By the way, the “real” in “a son is a poor substitute for a real love” was axed. This subject matter was obviously new for mainstream cinema in 1960, and the audience reactions ranged from slight titillation, which is what Hitchcock preferred, to complete shock.

Despite all these elements, it was the sexual and violent nature of the story and the way Hitchcock told it that dominated viewers’ thoughts, not the more subtle overall theme of being watched. Only when considering all the elements discussed as parts of the whole can this theme be fully understood. Admittedly, it is easier to do this today than in 1960, as the revised negative critical assessments prove. Understanding the theme also makes one aware that Hitchcock was more like his audience than most thought: curious, slightly scared of real-life conflict and desirous of a way to eavesdrop on the world to experience the drama he so loved without having to deal with its often disturbing outcome. Psycho allowed him and his audience to fulfill their desires of observing a fascinating, macabre world by becoming a fly on the wall without being swatted.

© 1994 MeierMovies, LLC

References

Brill, Lesley. The Hitchcock Romance: Love and Irony in Hitchcock’s Films. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Deutelbaum, Marshall and Leland Poague, editors. A Hitchcock Reader. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1986.

Hitchcock, Alfred, director. Psycho. MCA/Universal (orginal distributor: Paramount), 1960, videocassette.

Leitch, Thomas. Find the Director and Other Hitchcock Games. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

Mordden, Ethan. Medium Cool. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990.

Rebello, Stephen. Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. New York: Dembner Books, 1990.

Schickel, Richard, producer. The Men Who Made the Movies – Hitchcock. MPI, 1973, videocassette.

Spoto, Donald. The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983.

Wood, Robin. Hitchcock’s Films Revisited. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

For more information on the movie, visit IMDB and Wikipedia. And for modern photos of the old Jefferson Hotel, which was featured in the opening establishing shot of the movie, go here.