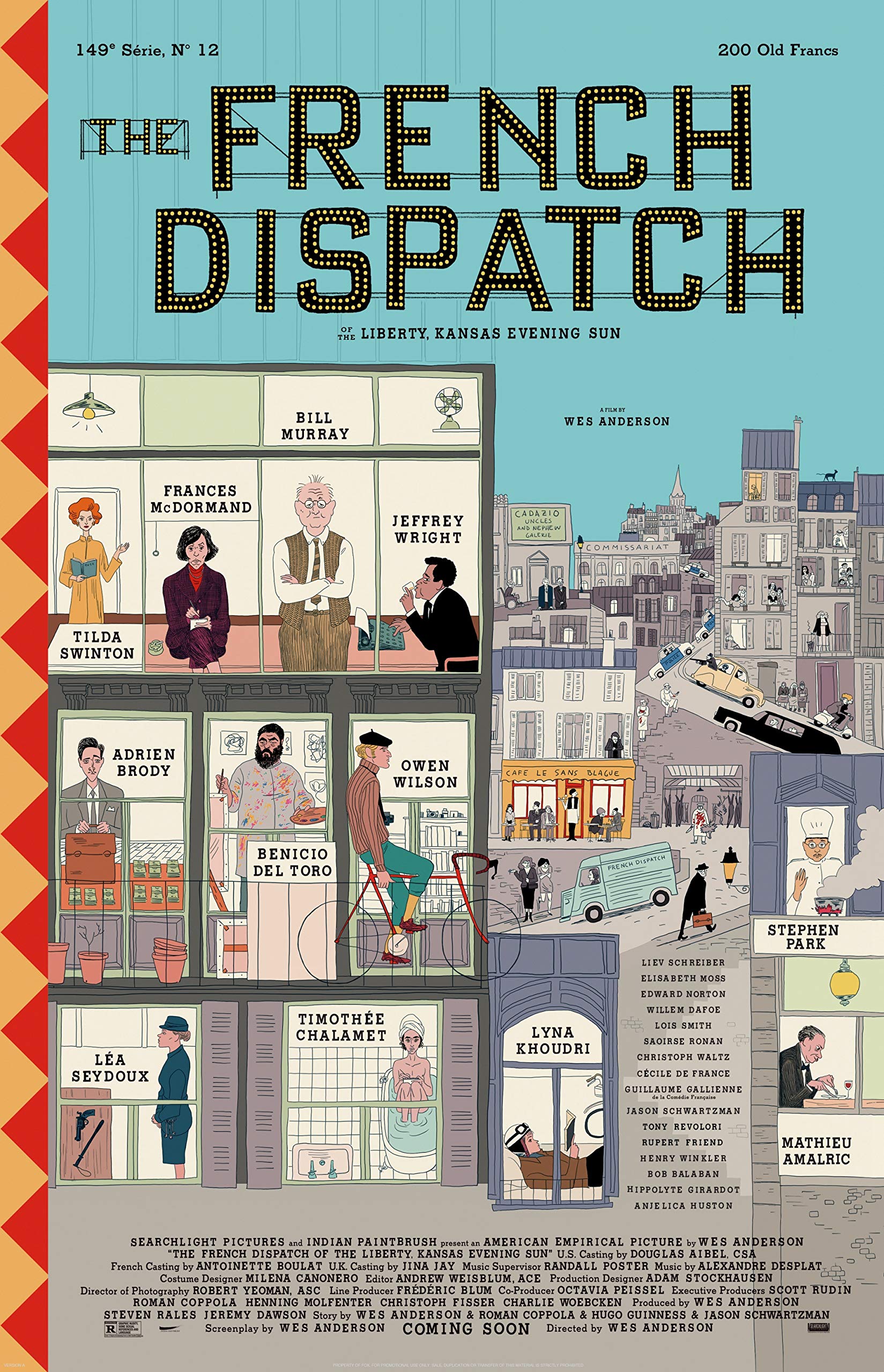

The French Dispatch

The French Dispatch, 2021, 2 ¼ stars

ADD club sandwich

Dispatch is Anderson’s most frenetic, multi-layered film

Exclusive to MeierMovies, October 22, 2021

Exclusive to MeierMovies, October 22, 2021

Wes Anderson, meet Carl Theodor Dreyer. Carl, Wes. You’ll hate each other.

Actually, as two of cinema’s master craftsmen, the two directors would likely enjoy wonderful conversations if not for the fact that Dreyer, the legendary Danish director of The Passion of Joan of Arc and Vampyr, died in 1968, the year preceding Anderson’s birth.

My reason for proffering this theoretical encounter is that the directors’ styles couldn’t be farther apart. Though their films are dominated by impeccable lighting, deliberate tracking shots, and OCD art design, Dreyer grew into a minimalist while Anderson is a maximalist – and getting maxier all the time. Case in point: The French Dispatch, Anderson’s dialogue-packed, attention-deficit-disorder club sandwich of an anthology comedy. And if you think that last sentence is overwritten, just wait until you get Dispatched.

In a 2019 interview, Anderson, in discussing Dispatch (which he wrote with help from Roman Coppola and Hugo Guinness), said, “The story is not easy to explain.” I second that. Actually, I fifth that, considering the film consists of three lengthy segments, one mini-tale (seemingly designed only to give Anderson darling Owen Wilson something to do) and a linking narrative featuring Bill Murray as the editor of the eponymous pamphlet, which, in a bit of a stretch in logic, is an off-shoot of the fictional Evening Sun of the non-fictional Liberty, Kansas, U.S.A. (Murray’s character is apparently based on Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker.)

The aforementioned mini-tale consists of Wilson (as Dispatch travel writer Herbsaint Sazerac) riding around on a bicycle in the fictional town of Ennui-sur-Blasé, France, where the film is set. In this respect, Wilson’s character is introducing us to the place we’ll soon by immersed in for 108 minutes. It’s a clever conceit but, like much of the film, gets buried behind an overpainted canvas. And as for the town’s name (translated roughly as “boredom on blasé”), it does show that Anderson is not taking all this too seriously. That’s helpful, but when the characters – most of whom are exhibiting Anderson’s trademark deadpan delivery – can’t work up much emotion about their own lives, why should we?

Wilson’s bike ride is followed by the meat of the film: an art story “written” (narrated) by a Dispatch reporter played by Tilda Swinton (as usual, with a crazy affectation); a political piece by another Dispatch reporter, portrayed by Frances McDormand, and featuring Timothée Chalamet, in a tale inspired by the French student unrest of May 1968; and a food feature served up by yet another reporter, played by Jeffrey Wright (whose character was partially inspired by James Baldwin). The first of the trio, titled “The Concrete Masterpiece,” is the strongest thanks to infectious performances by Benicio del Toro and Adrien Brody. The second and third tales are visually stunning, as is the entire opus, but get a bit lost in rushed and unimpactful storytelling. Indeed, we’re reminded of their raison d’être only in the film’s finale, when the reporters come together one last time to reminisce and honor Murray’s character, who has just died of a heart attack.

The aforementioned actors are the only ones allowed to fully shine, but Anderson peppers his stew with a slew of other famous faces: Elisabeth Moss, Jason Schwartzman, Henry Winkler, Bob Balaban, Léa Seydoux, Christoph Waltz, Liev Schreiber, Edward Norton, Willem Dafoe, Saoirse Ronan, Anjelica Huston (as part-time narrator) and even 90-year-old Lois Smith. Frankly, it’s one of the most impressive casts ever assembled, if only they had something to do besides scream silently to themselves, “Respect my cameo.” Perhaps it’s not a fair comparison, but contrast this to a Robert Altman film, in which every actor serves the story.

If you cock your brain just the right way or are an Anderson devotee, the film’s structure is almost brilliant – and, fittingly, quite French in its sensibility. But looking at it straight on – or from the vantage of either an Anderson detractor or just a casual fan – it’s exhausting and insufferable, with aspect-ratio alterations, doll-house tracking shots, changes from black-and-white to color and from live action to animation, and zoom-ins ad nauseam. It is overdesigned and underfelt. And though it’s impossible to deny its beauty, Dispatch is less a love letter to journalism, as Anderson intended, as one to Anderson’s own aesthetic.

Circling back to Dreyer: In his final film, Gertrud, from 1964, his minimalism had progressed so far that he eschewed even the most basic props of a realistic world, such as extraneous plates or spoons in a kitchen, opting to include only items that directly served his story. That might be taking things too far. Still, I wish that, just once, Anderson would run out of spoons.

© 2021 MeierMovies, LLC

For more information on this movie, visit IMDB and Wikipedia.